Many large meat-eating marsupials roamed Australia over the past millions of years, but the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, was the only one to survive into modern times. Together with Andrew Pask’s group at University of Melbourne, we are using cutting-edge techniques to reconstruct the life, growth and death of this recently extinct predator, including 3D digital imaging and ancient genome assembly. These methods provide new insights into the thylacine’s extraordinary position among mammals, such as its uncanny resemblance to wolves and dingos, its poor genetic health prior to the arrival of humans, and its relationship to other marsupials like the Tasmanian devil and numbat.

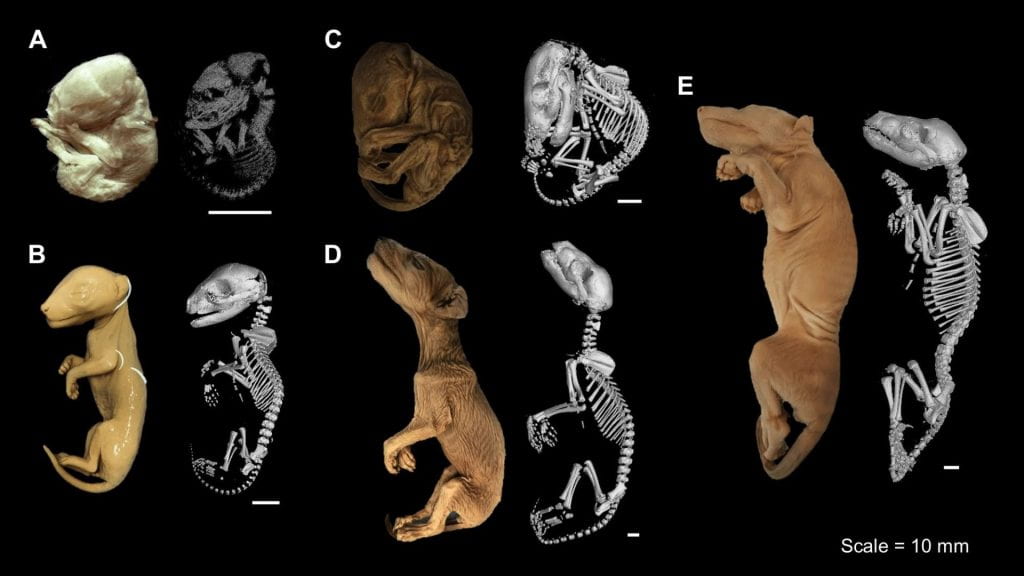

Our previous work established the marsupial thylacine as a model of phenotypic convergence with eutherian canids, despite the two groups being separated since the early to middle Jurassic, some 160-180 million years ago. We later determined, by reconstructing skeletal development of the thylacine using detailed bone measurements from CT scans of all known pouch young specimens in the world, that thylacines also grew, and likely moved, similar to a large cursorial (running) predator. Currently we are trying to identify exactly when and where thylacines diverged from their conserved marsupial development to take on the proportions of a eutherian canid, particular in features of the skull.

Our results have been featured widely in both popular and scientific press, showing that the public’s interest in this unique marsupial is still very much alive.